Two Saturdays ago, the Outliers rode the full length of the Watarase Ravine/Valley Railway (渡良瀬渓谷鉄道) in order to hike to the headwaters of the Watarase River (渡良瀬川), which runs right past our apartment in Ashikaga on its way to join the Tone River (利根川) and eventually the Edo River (江戸川) above Tokyo. We had long been impressed by the combination of public parks, levees, and other flood control measures along the river, and were aware of the devastating floods caused by Typhoon Catherine in 1947 (followed by Ion in 1948 and Kitty in 1949). But we were blissfully unaware of the river's earlier, manmade disasters.

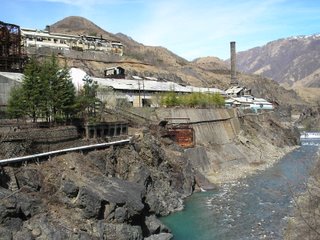

Two Saturdays ago, the Outliers rode the full length of the Watarase Ravine/Valley Railway (渡良瀬渓谷鉄道) in order to hike to the headwaters of the Watarase River (渡良瀬川), which runs right past our apartment in Ashikaga on its way to join the Tone River (利根川) and eventually the Edo River (江戸川) above Tokyo. We had long been impressed by the combination of public parks, levees, and other flood control measures along the river, and were aware of the devastating floods caused by Typhoon Catherine in 1947 (followed by Ion in 1948 and Kitty in 1949). But we were blissfully unaware of the river's earlier, manmade disasters.Our destination was the Akagane Water Control Park (銅親水公園 Akagane Shinsui Kouen)—billed as Japan's "Grand Canyon"—about a one-hour walk from the end of the tracks, which start from Kiryuu (桐生 < kiri 'paulownia' + u birth'?) along the eastern edge of Gunma Prefecture, and end at Matou (間藤 'room wisteria'?) in the Ashio (足尾 'leg tail') region of what was once Tochigi Prefecture's wild west (its Butte, Montana, in fact), but has just been incorporated into Nikko City, renowned for its tourist industry, not for its copper mines.

First the tale of the words, then the tale of the tailings.

銅 akagane (lit. 'red metal') 'copper, bronze' is more commonly read in its Sino-Japanese pronunciation dou, as in 銅山 douzan 'copper lode (= mountain)', 銅線 dousen 'copper wire', or 銅器時代 doukijidai 'Bronze (Utensil) Age'. Nevertheless, tourist maps almost always either spell the name in hiragana or gloss the Chinese character with its native Japanese reading—in both cases: あかがね.

親水 shinsui (lit. 'parent water') would seem a pretty good match for English 'headwaters', but I couldn't find the compound in my New Nelson kanji dictionary. Worse yet, my Canon Wordtank Daijirin defines it as 'affinity (親和性 shinwasei) or intimacy (親しみ shitashimi) with water', but then offers the prosaic 疎水 sosui 'drainage canal' as an alternate. A Japanese ecology word site gives a whole plethora of usage ranging from 'water encounter' to 'drainage ditch' to 'water projects'.

公害 kougai (lit. 'public damage') 'industrial pollution' is a more historically justifiable head noun for this compound than 公園 kouen 'public park'.

Kichiro Shoji and Masuro Sugai, two researchers at UN University in Japan, have published a detailed account of the rise and fall of the Ashio Copper Mine, parts of which are excerpted below to mark the 50th anniversary of the official recognition of Minamata mercury-poisoning disease, Japan's worst case of postwar 公害.

In 1868, the newly established Meiji government of Japan made the modernization of the country by increasing military strength and expanding industrial production its first national priority. The government established a Department of Industry in 1870 and came to control all industries other than the military. On the basis of land taxes, this new department took the initiative in starting new industries, and looking after private enterprise until the department was disbanded in 1885. The work that the department had done was to introduce new technologies and machines from the advanced capitalist countries and also to invite technicians to Japan to provide new industrial production models and technologies.

Related industrial laws were established and, by 1877, mining, financed by private capital, had grown rapidly. Copper was especially important for the new government, because its exports brought in much-needed foreign money. The demand for copper overseas supported the copper industry in Japan. As table 1.1 indicates, most of the copper produced in Japan was exported. Copper earned 9.5 per cent of Japan's export earnings in 1890 and through this Japan became established as a world-level copper producer. The earnings were used to purchase mining equipment, military weapons, and other industrial machinery. Copper played an important role in the development of Japan's capitalism, and the main domestic copper producer was the Ashio copper mine.

The Ashio copper mine had been the property of the Tokugawa shogunate, and as such had produced 1,500 tons annually, which was the maximum possible output in the 1600s. However, this high output level had been dropping gradually. The mine was temporarily closed in 1800, but in 1871 it became a private operation, and finally in 1877 it came to be owned by Ichibei Furukawa. In 1881 a new but small lode of ore was discovered, followed by a much larger one in 1884, and, as indicated in table 1.2, copper production rose very rapidly as a result of these discoveries. In 1884, the production stood at 2,286 tons per year. Thus Ashio became the mine with the highest output in Japan, producing 68 per cent of the total output of Furukawa mines and 26 per cent of Japan's production....

As indicated in figure 1.1, the discovery of the large copper ore lode caused all the trees surrounding it to die by the end of 1884. In August 1885. the use of a rock-crushing machine and a steam-operated pump in the Ani mine greatly increased production but led to massive fish kills in the Watarase River. In August 1890, when all modern technology systems had been installed, [a] flood occurred in the Watarase river basin, and 1,600 hectares of farmland and 28 towns and villages in Tochigi and Gunma prefectures were heavily damaged by the floodwater, which contained poisons from the Ashio mine.

In October 1890, Chugo Hayakawa led a movement against the mine and asked the prefectural hospital to do some tests for water-borne poisons. In December, the residents of Azuma Village, Tochigi Prefecture, appealed to the governor of the prefecture to call a halt to the mining operations at Ashio. This was the first of such appeals and of the movements against Ashio....

Essential to waging the Sino-Japanese War was an increase in iron and steel production. However, Japan's smelting techniques were still immature. From 1896 to 1900, Japan could meet only about 50 per cent of its demand for iron, and one-twentieth of that for steel. As a result, it was absolutely essential that Japan import iron and steel. In this context, the importation of refining equipment, weapons, and other steel-fabricating machinery was greatly increased, and the foreign money earned by the copper-mine output played an important role in paying for these foreign goods....

In September 1896 a massive flood, larger than the one visited on the area in July of the same year, was caused by torrential rains, and the Watarase, the Tone, and the Edo overflowed their banks. One large city, five prefectures, twelve provinces, and 136 towns and villages over a total area of 46,723 hectares were damaged by the water-borne mine poisons. The loss sustained was about 23 million yen, which was eight times the annual income of the Ashio copper mine.

Because of the seriousness of the mine-related damage to the natural environment, [Tochigi Prefecture Diet member] Shozo Tanaka set up a mining damage office in the Unryu Temple of Watarase Village in Gunma Prefecture, and with other volunteers began to take action to end operations at the mine. He started by organizing people in the areas most heavily destroyed, suggesting to them that the farmlands in the flooded areas be exempted from national taxes.

This was the beginning of one of Japan's first mass-based citizens' movements....

The flood of 1898 did even worse damage to the surrounding areas because massive amounts of slag had been released from the sedimentation pond built by the mining company. In extreme anger and frustration, over 11,001) farmers started out for Tokyo 26 September for the third mass demonstration, with demands for reinforcement of the river banks, for the sparing of the poisoned areas from further insult and for a policy of support for the bankrupt local governments. They were confronted on the way by the police and military forces. However, some 2,500 succeeded in getting to Hogima Village, Minami Adachi Province, Tokyo.

Although Shozo Tanaka had been sick at the time, he went to meet the farmers and advised them to leave 50 representatives with him and go back to their villages. Tanaka pledged that if their demands were not met, he would fight to the death for their cause. In this manner Tanaka became the leader of the struggle against the copper mine and began to organize the farmers....

The Mainichi shimbun published a series of articles, written by women journalists, on the miseries brought about by the copper-mine poisonings. Related news articles on the struggles of the people were also printed, and the editorials took up the cause. On 30 November, Tameko Furukawa, the wife of Ichibei Furukawa, took her own life by drowning under the Kanda Bridge.

On the morning of 10 December 1901, when, after presiding at the opening of the sixteenth National Diet Upper House session, Emperor Meiji was going to his carriage, Tanaka came up to him, a written appeal in hand, shouting to him. By this action Tanaka had planned to bring the scandal of the mine poisonings into public view, hoping that one of the imperial guards would either kill or injure him. But in fact, the sergeant-at-arms fell from his horse, which had reared up in surprise, and Tanaka also stumbled and fell on his face, so he was neither killed nor injured. He was arrested on the spot and taken into custody by the police....

Tanaka's appeal did not work as planned. but it astounded the public at large. Many people from different walks of life began to involve themselves in attempts to improve the terrible situation caused by the mine poisonings. On 27 December 1901, a trip to the poisoned areas was planned and about 800 students from 40 colleges, universities, and high schools joined it. They were deeply moved by the damage done to the environment, and so they organized movements designed to spread the news about the grim reality of the destruction and the need to help the farmers. This was the first of the numerous student movements that were to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment