ハリセンボン (針千本) harisenbon - Newly relocated Makishi Market had many colorful reef fish for sale, along with a cornucopia of pig parts (ears being a uniquely Okinawan favorite). Among the fish was one I had never seen for sale before, a porcupine fish (labeled harisenbon 'thousand needles'), usually sold with its spiny skin peeled off. We didn't get a chance to eat it.

フリソデ (振袖) furisode - At a yakitori bar specializing in Miyazaki chicken and Kyushu sweet-potato shochu, we encountered a menu item new to us, labeled furisode 'swinging-sleeve', which most commonly labels the deep sleeve pockets of kimono. (Furi 'swing' also appears in karaburi 'empty swing', the term for a swing-and-a-miss in baseball.) After consulting the chart of chicken cuts on the wall, where the furisode is right above the sunagimo (lit. 'sand-liver') 'gizzard' and rebaa 'liver', it finally dawned on us that furisode is a fancy name for a chicken's crop, for which the technical name in Japanese is 素嚢 sonou lit. 'simple/first-pouch'. We ordered a skewer of it, and also tried their chicken-liver sashimi specialty item. The other customers were mostly drinking, so the chef and young waitress were very pleased to see how much we enjoyed the fine foods prepared, and gave us several items not on the menu (like skewers of roasted garlic cloves).

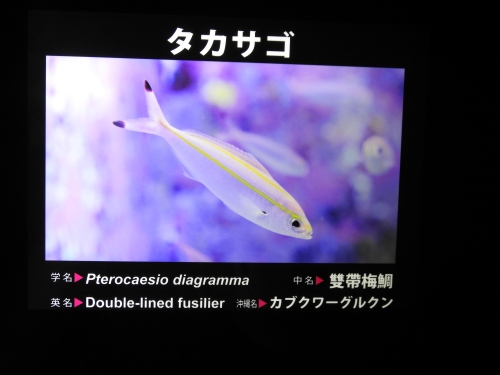

グルクン gurukun 'double-lined fusilier' - We ate the popular prefectural fish of Okinawa, called gurukun there, but タカサゴ (高砂) takasago in Japanese during our first excursion to Makishi Market. The fish sellers there generally recommend eating their fish either raw (as sashimi) or deep-fried (karaage), because reef fish are not as oily as the fish most favored for shioyaki (salt-roasting). Many of the larger reef fish were individually speared, judging from the holes through their eyes or head, but large numbers of the smaller gurukun are often herded or chased into a net by a team of divers.